The circle above shows the themes about effective knowledge exchange that emerged from our analysis of interview transcripts. It shows how they map onto the five principles in the table above. Each of these themes are summarized in the table below in greater detail, based on the words of those we interviewed.

Design

Aim high but be realisticAiming high can achieve a lot. However, if expectations of project outcomes are set too high participants may become frustrated by lack of progress. Aim to maintain a balance between presenting the best possible scenario and being realistic about what can practically be achieved.

Be transparent Act with honesty. It is important that all involved know the objectives of the project and what their role is likely to be as well as the project outputs and any recognition they may gain from their involvement. Time spent at the beginning introducing each other and sharing personal motivations and goals is helpful.

Context Understand the context of the project. Understand local characteristics, traditions, norms and past experiences, use this as a starting point for planning the project. Some projects have found it useful to carry out ethnographic research prior to project commencement to ensure planning best matches context.

Dedicated KE time KE is time consuming if done properly. If not done properly bridges can be burnt that will influence not only the effectiveness of the present project but projects to come. Dedicate time specifically for KE. Even better, have a KE officer involved in the project.

Design the KE process well It is vital to plan the KE process well. Spend time researching the context, the stakeholders, and possible approaches. Look into alternative approaches in case the approach selected fails. Design for flexibility and to incorporate feedback and design to suit the circumstances. It is best to plan to use a range of methods and approaches in the design.

Early bird catches the worm Knowledge Exchange must be started early in the project. Ideally planning and research into the context and stakeholders should begin prior to project commencement.

Embed KE KE is not just an activity to be carried out a certain points in a project. To be effective KE must be planned for and included throughout. In designing activities projects must evaluate their KE progress and how effective they have been.

Get Buy in Ownership and ongoing commitment can be quickly established by getting ‘Buy In’ from the key stakeholders involved. This can be in the form of monetary investment or contracted time to the project. Buy in is especially important from those high up in organizations.

Independence Ensure that the management of the project is seen as independent/neutral. This can be achieved through an independent/neutral organization leading the process or an independent facilitator being on board. Independence can help build trust in the process and speed KE.

Mixture of methods Plan to use a variety of methods. Different people will enjoy and be best suited to different methods. Always start with those methods that will be the most comfortable to stakeholders, as trust builds more innovative methods can be used.

Plan for Flexibility Avoid inflexible methods and strategies when planning a KE process. Leave space within the plan to adapt methods and approaches as required.

Prepare properly Successful KE processes are those which have had significant time spent in researching the context of the project, the individuals involved and the methods and approach to take. They are also the projects that have anticipated the amount of time and resources required for effective KE.

Process is as important as product How a KE process is implemented often is as important as the end result. Ensure proper attention is paid to creating an effective KE process. However, most KE processes are in place to achieve a goal so, ensure you keep that goal in sight!

Select the right team Take into account personalities, attitudes and worldviews of the KE core team. Teams with a similar world view and complimentary personalities will work well together irrespective of discipline. In particular select teams which are used to working across disciplines and value all different types of knowledge. Teams that have worked together in the past may work best as less time is taken in understanding one another.

Spend money on KE KE processes take up significant time and resources. There are methods available for low budgets that are reliant on the teams personal time and energy. However, if budgets are too low corners may be cut and results will be less significant. Money spent on a well designed process, that budgets for social events, KE officer, facilitator, refreshments and stakeholder compensation may be more expensive in the short term but are the most likely to achieve long–term behavior change not only for those involved but for future generations that can benefit from improvements to knowledge and infrastructure.

Tailor approach Tailor your research approach to the kind of impact you want to have i.e. if you aim to influence policy identify the key policy areas and work to those. Likewise tailor your communication to closely match the communication strategies of the organizations/individuals you most want to affect.

Understand what everyone wants Spend time understanding what the stakeholders and project members want from the project. This can help in managing expectations and identifying potential issues/problems early on.

Engage

Away days Put time aside at the start of the project for the core team/group to get to know one another’s disciplines, background and languages. Include time for socializing.

Be enthusiastic Enthusiasm for the process and approach is easily transferred to those involved. Enthusiasm can go far in helping to maintain momentum and achieve participant long-term involvement.

Be honest Be honest throughout the process, about the goals of the activity and practical implications of involvement. Most participants are motivated by the chance to make a difference, but if this is unlikely to be possible make it clear from the outset. Be honest with participants about what they will gain through participation. Do not have a hidden agenda.

Build capacity for engagement Spend time in the project building the capacity of those involved in order to operate the process on a more level playing field. Aim to create a shared skill base and include basic training activities in the project early on to improve knowledge exchange and co-production.

Build personal relationships KE is all about relationships. Without relationships KE is ineffective. Spend time building relationships. Time to socialize is just as important early on in a process as time spent on KE activities. Schedule in social time in the project and get to know participants on a one-one basis.

Build Trust Lack of trust will reduce how effective KE is. Spend time explicitly considering Trust levels in the project and how to improve trust. A number of activities can help build trust. In general trust building takes time and is closely relating to building relationships and being honest and transparent.

Multiple modes of communication Let the wider local community and policy makers know what you are doing and if possible how they can get involved. Use of a website is particularly helpful for this, although new forms of web 2.0 technology such as twitter, facebook and youtube are also effective. Newsletters keep participants up to date. Try to use a range of different methods to communicate both internally and externally.

Compensate A barrier to involvement can be loss of income for those involved. If possible offer compensation for lost earnings. At the very least ensure that participants are compensated for their time by being provided with adequate meeting facilitates and good quality refreshments.

Keep in people’s comfort zones Be aware of what is comfortable for those involved and keep within their comfort zone. Have meetings in the local area and in a non-threatening, neutral environment. Choose activities (at least initially) that stakeholders are comfortable with.

Don’t rush it Rushing KE is problematic as individuals take different amounts of time to build trust, confidence, to learn and to share knowledge. Time may need to be built in for reflection. However, KE projects do need to pay attention to deadlines. The use of facilitators, local knowledge brokers and activities to keep on track can be helpful.

Enjoy! Make sure the process is enjoyable and interesting for yourself, the team leading it and those involved. Pay attention to designing enjoyable activities.

Keep it simple Do not assume levels of literacy or education. Keep language and approaches simple and accessible. Spend time discussing and agreeing terms to be used, and the best approach to take. Involve skill sharing so that all participants gain a shared basic understanding, for example, by involving participants in G.I.S. work or spending time work shadowing gamekeepers. A stakeholder steering group may help in ensuring the language and approach is suitable.

Work around people’s commitments The most challenging aspect to KE processes ensuring participants stay involved. Stakeholders nearly always have other commitments and may have seasonal differences in work patterns. Consult with stakeholders as soon as possible to match process to commitments. It might work best to have morning meetings rather than evening meetings and certain times of year may not work well for attendance.

Manage power dynamics Power dynamics can have a significant impact on a process. It is incredibly important to recognize that power dynamics play a role in the process and to plan for and manage this appropriately. For example, ensuring a first name basis can go some way towards balancing power but it is still important to recognize that others will be conscious of who is a professor, a Dr. or a Sir. and will be adapting their behavior and communication as a result.

Record In order to ensure transparent, trustworthy processes make sure that your KE process is properly recorded. This is also important in order to identify and learn from methods that have been particularly successful or unsuccessful. However, do be aware of methods of documentation, some participants may be uncomfortable with audio or video recording.

Keep your goals in mind Reiterate project goals throughout the process and keep to deadlines.

Respect cultural contextMake sure that your approach is suitable for the cultural context in which you are working. Consider local attitudes to gender, informal livelihoods, social groupings, speaking out in public and so on.

Respect local knowledge All participants will have significant knowledge of their community and will be capable of analysing and assessing their personal situation, often better than trained professionals. Respect local perceptions, choices, and abilities and involve all types of knowledge when setting goals and planning research.

Share responsibilities Share out responsibilities and credit in order to help build relationships, trust in the process and foster ownership for those involved.

Use a facilitator Effective group management is incredibly difficult and requires a professional facilitator Without good facilitation the most articulate and powerful may dominate and the process will be unable to achieve effective knowledge exchange. Ensure those running the project have good facilitation skills, if they do not hire a trained facilitator for this.

Use knowledge brokers Make use of the local community. Take time to identify individuals that play a significant role in the community and can act as a local champion. Such individuals will be well linked and able to understand different types of community’s perspectives. Involvement of a knowledge broker will help develop local capacity, build trust and increase long-term sustainability.

Visualise Aim to present information visually rather than in words. Tools that use maps, illustrations, cartoons, drawings, photos and models are particularly successful in KE processes.

Work outside when you can Wherever possible, have KE activities physically in the area being discussed. Field trips are particularly valuable, especially if coupled with stakeholder hosting to increase ownership. Working outdoors makes it easier for all to articulate complex concepts and understand the reality of a situation.

Represent

Involve the right peopleSpend time researching which stakeholders are best to involve. A systematic method such as stakeholder analysis can be incredibly useful for this, discussion with an established institution with significant understanding of context and people in the area of the KE project may be equally fruitful. Make sure power dynamics between individuals are considered and attention paid to selecting individuals who can make a difference. Involve all parties as early as possible, preferably in the planning process. Time spent in one-one discussion to win over those who doubt the value of the process before you start is well worthwhile. If there are people or groups, who cannot be convinced at the outset, keep them informed and give them the option of joining in later. Remove individuals from the process that are particularly disruptive.

Not just the usual suspectsTry not to only include the ‘usual suspects’. Those of different ages, gender, backgrounds and cultures bring different knowledge, concerns and perspectives. By representing the diversity of a community in a well designed process a project can have a far greater long term reach and sustainability.

Understand and create networksUnderstand the social networks that the people you want to work with are part of. Spend time creating connections both vertically and horizontally. Aim to create networks where possible between the interest groups involved as well as with potential funding sources in order to help maintain achieve the potential for long term resilience.

Personal initiativeMany effective KE processes are based on one individuals initiative. KE processes require at least one individual to push the process through and maintain momentum.

RelevanceSpend time finding what everyone wants out of the process and ensure the process is relevant to those involved.

Understand different motivationsPeople are motivated to become involved in a KE process for a number of reasons, for instance: academic exploration and gain, interest, to learn, fear, financial gain, professional duty, personal promotion, and support of the local community. It is important to take steps to make personal agendas explicit, perhaps through anonymous ballot at the start of the project or explicit discussion.

Impact

Deliver quick winsEnsure that if the project aims to create practical outcomes it delivers on these. Delivery of practical outcomes is a key motivator for involvement and identifying ‘quick wins’ for delivery early on can help build trust and relationships, improving the effectiveness of KE activities.

Work for mutual benefitWork hard to ensure that the project is of mutual benefit. Spend time finding out what people want from the process and try hard to deliver this. Unbalanced processes, for example, those which appear to be all about academic benefit can fail to get the best from those involved and can affect trust and commitment to the process.

Reflect and sustain

Get participant feedback regularly Ensure that you get feedback throughout on activities and participants concern’s/ideas. Such feedback will help the project to adapt techniques and deal with problems as they arrive to improve effectiveness.

Make time for reflection Build in time for all involved in KE activities to reflect on the process and outcomes. This is especially important when working in areas of conflict to ensure optimum learning and behavior change.

Learn from others good at KE Spend time exploring similar work and institutes within an area. Don’t assume absolute knowledge over others. Include well known institutes and people and let them take a lead in running meetings and events. Go and visit other successful KE projects and speak to people who have carried out similar work. It may be useful to engage a mentor from a KE project you admire and ask them give feedback on your process as you go along.

Continuity of involvement Continuity of people involved is incredibly important, especially for projects dealing with some form of controversy. By including the same group of individuals critical relationships and trust develop which facilitate effective KE. Continuity of project meetings is also important. Having meetings at regular intervals embeds the project and increases chances of continuity in attendance.

Follow-up on KE success The majority of current projects do not follow up on the success of KE activities. This is usually due to a lack of requirement or budget to do so. Put time and resources aside in your KE project plan for documenting, publicising and delivery.

Local ongoing ownership of process The majority of KE processes aim to achieve long term behavior change. In order to ensure such change local people must be enabled to take responsibility. Projects should spend time integrating the community into decision making and research and ensuring the relevant skills are passed on. Employing a local community member onto the team can be a useful technique.

Maintain momentum Regularly monitor progress to ensure that initiatives are built on and objectives achieved or altered as required. KE processes are lengthy and often take unpredictable turns. If there has to be a break, start from where you left off and build this into the process. It may be useful to call break a period for reflection and present it as part of the process. Review sessions, feedback forms and good facilitation can ensure that momentum is maintained.

If you want to find out more about what it takes to be great at knowledge exchange, and gain confidence using these skills, check out the not-for-profit training we do, which is based on this research. So far we’ve trained researchers from >20 Universities and research institutes across the UK and in Europe, and have trained research managers from Government and the Research Councils. Our goal is to build capacity for knowledge exchange across the research community, so we can put our ideas into practice and be the change we want to be.

Prof Mark Reed is an interdisciplinary researcher specialising in knowledge exchange, stakeholder participation and the value of nature. He obtained his PhD from the University of Leeds, where he was a Senior Lecturer till he became Director of the Aberdeen Centre for Environmental Sustainability at the University of Aberdeen. He is now a professor at Birmingham City University, where he is led the REF submission for his School. He has over 100 publications (>60 in peer-reviewed international journals). His work has been covered by the Guardian, Radio 4, Radio Scotland and international media, and he has led research projects worth over £10M. He has designed and led >50 workshops with end users of research in the UK and internationally, and has developed training in knowledge exchange and participatory methods for the UN Environment Programme, DEFRA, Scottish Government, the British Ecological Society and a range of UK Universities. Find out more about his work at: www.profmarkreed.com or follow him on Twitter @profmarkreed

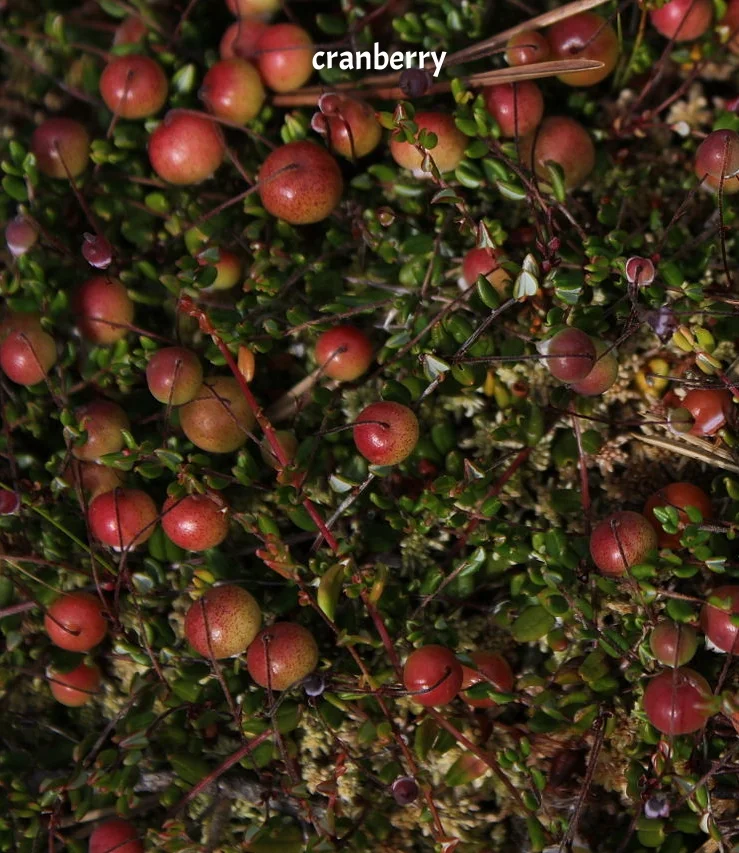

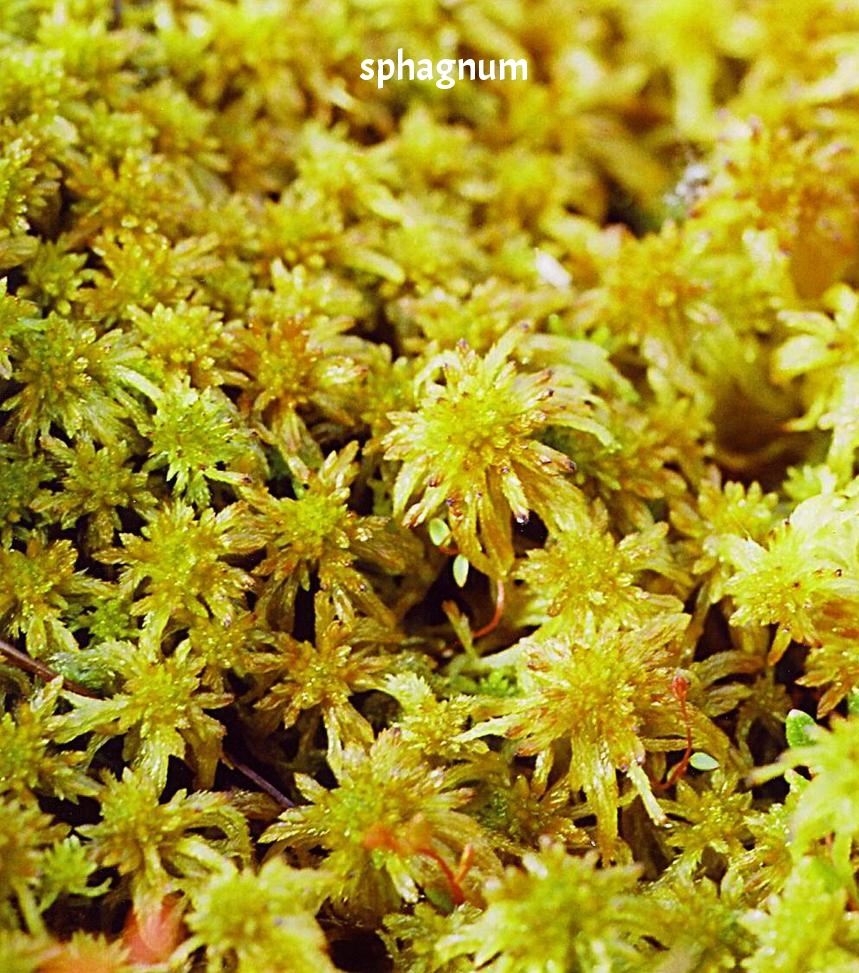

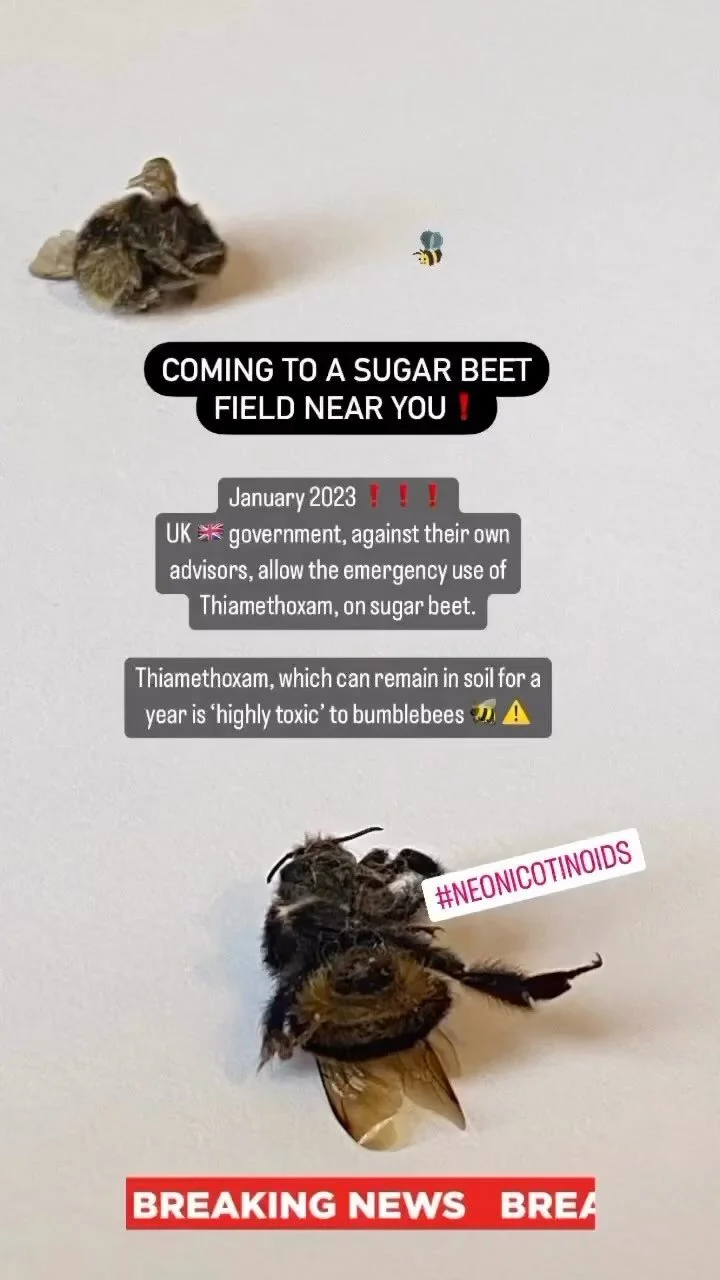

Dr Ana Attlee is co-founder and director of international eco enterprise Project Maya. Ana’s background is in sustainability and conservation she is passionate about social media and permaculture. Ana is an interdisciplinary researcher/campaigner/entrepreneur. Academically she continues to work with the Sustainable Learning project on Knowledge Exchange and has published on environmental sustainability and behaviour change. She recently launched ‘Seedball’ as an innovative way to raise funds for Project Maya, has been involved in using social media for crowd funding projects (raising funds for meadows outside tube stations in London) and campaigning (for road verges to become wild flower reserves). Before founding Project Maya, Ana worked as a lecturer, post-doctoral researcher and conference organiser and has acted as an advisor on social media strategy to a number of academic institutions and charities. Find out more about her work at: www.annattlee .com or follow her on Twitter @AnaAttlee.